This report was originally published at Politeia Research Foundation on March 28, 2023.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict, growing demands for deglobalisation, the aggressive rise of China, climate change, territorial contestation of seas and oceans, and a faltering liberal accord are causing significant changes in the world order. In short, the contemporary world order is in flux, balancing between asymmetric multipolarity and prospects of an imminent bipolarity. To preserve multipolarity amidst growing threats of bipolarity, the democratic forces of the multipolar world ought to work together not only to avert fragmentation of the world order but also to rein in the powers that are on a quest to further the division.

The European Union is a very crucial democratic pole in the contemporary multipolar world because of its combined economic might, its democratic credentials, commitment to rules-based international order, and its role as a norm-setter of the world.The Union continues to be a major force in the world economy which is evident in the export ratio (ratio of exports of goods and services to GDP) and the import ratio (the ratio of imports of goods and services to GDP)of 49.2 per cent and 45.3 per cent respectively in 2019. However, the European Union is also beset by many challenges.

Besides the threats mentioned above, the European Union is also characterised by an increasing difference of opinion between members of the Union on matters of global relevance.For instance, the rise of right-wing parties and their growing influence has led to scepticism about the positive impacts of European integration on national economies.Moreover, critics argue that there are multiple internal divisions within the 27-member European Union, and safeguarding the integrity of the Union and the single marketwill be difficult in the increasingly polarising world order. The European Union’s worldview, as a result of a consequent increase in internal and external threat perceptions, is in a state of churn. Therefore, the need for a comprehensive and joint global strategy was evident if the 27-member Union had to preserve its clout in the world economy and security landscape.Hence, looking at how the European Union evaluates the world order is crucial.

The Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy, launched in 2016,was a step in that direction.Federica Mogherini, the former High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy,argues, “in challenging times, a strong Union is one that thinks strategically, shares a vision and acts together”. The EU Global Strategy further asserts that Europe would “navigate this difficult, more connected, contested and complex world guided by our shared interests, principles and priorities.” However, the intensity of the challenges alluded to increased between 2016 and 2023. Therefore, it is imperative to take a re-look at the pronouncements of the European Global Strategy in the context of the churn that has occurred in world politics since 2016. Strategies need a dynamic assessment of the landscape.Determination of attainable objectives is crucial to any strategy. The EU Global Strategy delineates the following key priorities for its foreign and security policy.

- The strategy acknowledges the requirement for protection from “terrorism, hybrid threats, economic volatility, climate change and energy insecurity”.The EU calls for working closely with partners such as NATO members while preserving its strategic autonomy.

- It emphasises the requirement for state robustness and dependability in the EU’s peripheral area, reaching Central Asia in the East and Central Africa in the South.Resilience has been exhaustively conceptualised, focusing on “governmental, economic, societal and climate/energy fragility”.

- It calls for an integrated approach to conflict across all stages of the conflict cycle, from prevention to response and reconstruction.

- The strategy calls for the effective engagement of cooperative regional orders.

- Global governance grounded on international law and collaboration regarding global commons has also been underscored.

The coreprinciple or the essential rule also plays an indispensable role in constructing the approach towards fulfilling the objectives established by a strategy. The illuminating beacon of principled pragmatism directing the EU’s external action has been aptly expressed by the following sentence from the strategy document: “In charting the way between the Scylla of isolationism and the Charybdis of rash interventionism, the EU will engage the world manifesting responsibility towards others and sensitivity to contingency.” Unity within the EU, engagement with external players, responsibility to address conflict, destitution and human rights violations, and partnership with like-minded countries have been delineated as the core principles of external engagement by the EU Global Strategy.

Cooperative Regional Orders

Having specified the leading principles, the EU Global Strategy outlines the five central objectives or main points of external action. The five objectives have been previously mentioned in this essay. This essay shall henceforth delve deeper into the “cooperative regional orders” segment of the strategy document and attempt to understand and revisit the European perspective of regional orders and cooperation.

The EU sees itself as an example of a successful cooperative regional order, and the strategy states that the voluntary form of regional governance “is a fundamental rationale for the EU’s peace and development in the 21st century.” The EU Global Strategy asserts that cooperative regional orders are created not only by organisations but also by the complex web of “bilateral, sub-regional, regional and inter-regional relations”. However, the strategy also recognises that regional orders may assume multiple forms and that imposition of the EU regional governance model may not be desirable for other regions. Every regional governance architecture may organically imbibe the beneficial aspects of the other regional orders through “reciprocal inspiration” and “cooperative relationships to spur shared global responsibilities.” The strategy delineates five key regional security priorities vis-à-vis a stable and peaceful European regional order. The regions are:

- European region

- Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa

- Trans-Atlantic region

- North Atlantic

- South Atlantic: Latin America and the Caribbean

- Asia

- Arctic

The European Union’s Scylla

First, the document identifies Russia as a strategic challenge and argues that “Russia’s violation of international law and the destabilisation of Ukraine, on top of protracted conflicts in the wider Black Sea region, has challenged the European security order at its core.” Despite the accurate diagnosis of the threat, the way events unfolded between the annexation of Crimea in February-March 2014, and the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in February 2022 show that Europe’s interdependence on Russia made any pre-emptive balancing toothless. Russia was, thus, emboldened to launch another offensive against Ukraine despite the securitisation of the Russian challenge in Europe following the Crimean crisis. Europe, some might argue, was caught napping. Although as the Russia-Ukraine conflict unfolded, Europe indicated resolve to stand up to Russia. However, Europe standing up to Russia was more preventive than pre-emptive.

Belgian, EU and Ukrainian Flag. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Belgian, EU and Ukrainian Flag. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A conspicuous question that the European Union should contemplate is whether and when it can accept Ukraine’s membership application to join the fold of the EU countries. While all the powers within the European Union do not believe this is a conducive time to initiate the process of accession of Ukraine to the European Union, at least eight presidents have called for immediate talks on Ukraine’s membership of the EU. Notably, these are the presidents of Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. The European Union is a complex organisation, and accession is an arduous task contingent on various reforms that the Ukrainian government may have to undertake to join the Union. Expediting Ukraine’s membership has also been complicated by the war, which would make reforms in Ukraine even more difficult. Thus, Ukraine’s membership of the EU will be slowed down by at least two immediate challenges: the inability to agree unanimously on whether Ukraine should accede to the Union within strict timeframes and the procedural complexity of the reforms being contingent on reforms within Ukraine.These complex questions will continue to perplex European foreign policy actors at a time when a lot depends on getting the answers to these questions right.

Turmoil in the EU’s Extended Neighbourhood

Second, political turmoil and instability in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Africa are crucial threats to Europe since the turmoil could have spill-over effects such as terrorism and migration into Europe. The document argues that cooperation must be multi-layered, including sub-regional, regional, and multilateral frameworks, including the state and civil society. The fivefold action agenda for the regions includes supporting functional multilateral cooperation in the Maghreb and the Middle East; deepening cooperation with Türkiye while calling for more democracy in the country and normalisation of its relationship with Cyprus; ensuring deeper engagement with the Gulf Cooperation Council; fostering “triangular relationships across the Red Sea between Europe, the Horn and the Gulf”; and investing in African peace and development through support for “the African Union, as well as ECOWAS, the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development in eastern Africa, and the East African Community.

The EU’s policy in the extended neighbourhood continues to grapple with migration, terrorism, extremism, and instability. The migration question is complex because it has implications for external relations and affects the internal politics of the EU. The EU has agreed to restrict visas for countries failing to cooperate in taking their citizens back. The problem of a low effective return of immigrants has become a cause of concern owing to its impact on domestic and international politics. Irregular immigration into the EU owing to the crisis in its extended neighbourhood has also raised questions about the fairness of sharing the task of providing for those who have already entered the EU.

The Middle East and North African (MENA) and Sahel regions are also under pressure due to terrorism and extremism, which impacts European Security to a considerable extent. For example, in the Sahel region, France was cajoled into withdrawing from Burkina Faso and Mali. However, insurgency, extremism, and terrorism continue to fester in the region. Moreover, the Sahel region is crucial for the European security order because it “is being used as a transit hub for the trafficking of illicit goods—and people—to Europe”. The issues of instability and turmoil in the extended neighbourhood are further complicated by the involvement of Russia in the politics of MENA and Sahel, which also continues to concern the European Union deeply. Thus, according to several actors in Brussels, the problem of regional turmoil is also intrinsically linked to the involvement of Russia in the MENA and Sahel regions. No wonder Sahel has been labelled as the second front of Russia.

The extended neighbourhood story of the European Union will have to be dealt with deftly if the European Union is to retain its resilience against internal problems such as refugee sharing and management among states as well as external shocks such as uncontrolled immigration, extremism, terrorism and trafficking.

Transatlantic Ties: Crisis-induced Reinvigoration

Third, Transatlantic relations are a key prerogative for ensuring a stable and peaceful regional order. The document’s focus on Transatlantic relations goes beyond a narrow view of NATO and the defence and security aspects related to it. To the North of the Atlantic, it calls for efforts towards a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the USA. However, the grand project failed to pick steam. Transatlantic relations weakened under President Donald Trump, and the European Commission declared in April 2019 that the negotiating directives for TTIP were “obsolete and no longer relevant”. The rosy story of Euro-USA bonhomie remained elusive between 2014 and 2022. While Europe and the USA were still bickering over the broader trajectory of Transatlantic relations, the Russians launched an offensive in Ukraine, ultimately jolting the Transatlantic bloc into joint cooperative action. The post-facto coordinated response to the Russian state came about only after NATO’s deterrence could not cajole Russia into non-aggression.

To the South of the Atlantic, however, sustained vigour was seen in the European Union and Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) relations on a wide-ranging set of agendas such as energy cooperation, digital alliance, food markets, research and innovation, climate change and organised crime. The EU also deepened ties with CELAC by announcing new programmes to further the cause of sustainable development in the region to the South of the Atlantic. The EU-Mercosur relations also blossomed as the parties “reached a political agreement on 28 June 2019 for an ambitious, balanced and comprehensive trade agreement”.

On the Transatlantic front, the EU must maintain the vigour that the Russia-Ukraine conflict has again lent to its Transatlantic relations. However, in the quest to manage the Scylla of Europe, the EU and the USA should maintain sight of the Charybdis of the Indo-Pacific. Given the belligerent and irredentist rise of China in the Indo-Pacific, which has shown an utter disregard for international law, the USA and its allies cannot afford lesser attention to Indo-Pacific due to the European distraction. The EU, NATO and the USA stand on the horns of a deeply troubling dilemma.

Charybdis of the Indo-Pacific

Fourth, on the Asian landscape, the document exhibits a caution-driven outlook towards China. While the strategy document puts forward that “the EU will deepen trade and investment with China” and push for “greater cooperation on high-end technology”, it also highlighted that it was equally important to do so while “seeking a level playing field, intellectual property rights protection” and dialogue on “human rights.” Since the document’s release, EU-China relations have gone downhill due to emerging irritants such as the EU’s sanction on China because of the sorry state of human rights in China. China’s economic countermeasures, coercive geoeconomics and weaponisation of trade have soured relations. The EU also does not appreciate China’s ostensible ambivalence towards the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In reality, China tacitly relays support to Russia through intelligence sharing and export of semiconductor chips and “navigational equipment, jamming technology, radar systems, and fighter-jet parts”. However, a big economic bloc, like the EU, also relies on the Chinese economic powerhouse to ensure growth and prosperity within the bloc.The dilemmas of the EU vis-à-vis China are as Hamletian as India’s China dilemma. The dilemma revolves around balancing deeply entrenched economic relations with China while engaging an increasingly bellicose and belligerent strategic actor which has scant regard for mutual agreements, human rights and international law.

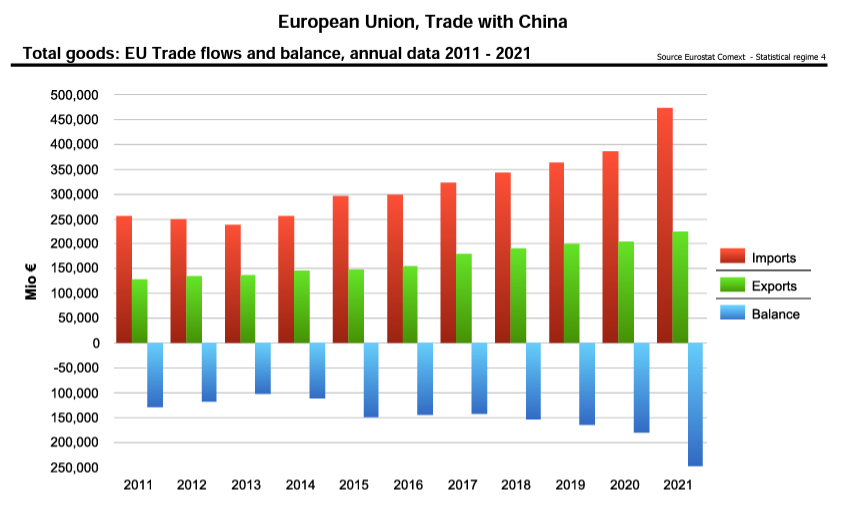

Figure 1: Trade between EU27 and China

Figure 1: Trade between EU27 and China

The EU’s dilemma can only be resolved in the long run by forging strategic partnerships with other actors in the Indo-Pacific such as India, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN. The trajectory of India’s partnership with the EU is on the right track, with growth in both trade and investment figures. In consonance with the strategy, the EU has relaunched talks on the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with India. Separate agreements on investment protection regimes and geographical indications are also being discussed simultaneously. Similarly, the EU’s engagement with ASEAN deepened after December 2020, when the ties were upgraded to a strategic partnership level. The EU has also recognised the principle of ASEAN centrality through its strategy document on the Indo-Pacific. With Japan and South Korea, the EU has continued to deepen ties through strategic partnerships and multi-faceted engagement across the full spectrum of relations. However, despite growing interactions, it is also noteworthy that Europe’s engagements with the Indo-Pacific countries are only at an incipient stage andare often piecemeal, as per a policy brief published by the European Institute for Asian Studies (EIAS). Notably, the Global Strategy of 2016 has not given due attention to the tempest brewing in the Indo-Pacific. However, five years after the 2016 document, the EU released an Indo-Pacific strategy in 202, which needs to be studied to develop a nuanced understanding of how Europe looks at the region.

The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, hereafter called the Indo-Pacific strategy, calls for sustainable development based on the principles of “democracy, the rule of law, human rights and international law”. In the Indo-Pacific strategy, the EU has identified the following areas of priority:

- Sustainable and inclusive prosperity, which focuses on developing trade relations with high standards of protection against unfair practices

- Green transition, which intends to focus not only on mitigation but also on adaptation

- Ocean governance, which stresses compliance with international laws such as UNCLOS

- Digital governance and partnerships with like-minded partners

- Digital connectivity under fair regulatory standards

- Security and defence, which focuses on securing SLOCs, naval deployments and cybersecurity

- Human security, which focuses on healthcare resilience and disaster-management

The priorities, although ambitious and directionally sound, will have to waddle through the challenges of difference in opinion among the member states of the EU vis-à-vis the idea of the Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, the interests of various countries within the EU do not tend to align vis-à-vis the Indo-Pacific, which could further complicate the pursuit of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Therefore, for effective implementation of the EU’s strategy, members ought to find common ground, first of all, on the geographical extent of the Indo-Pacific.

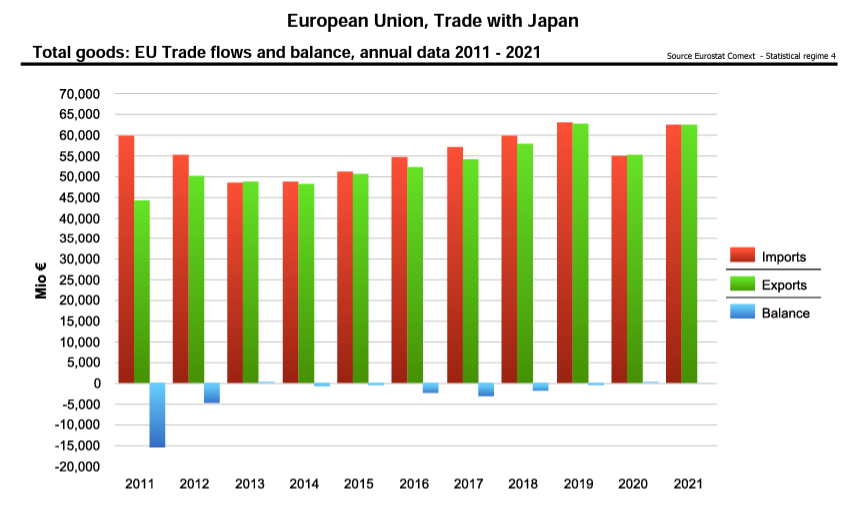

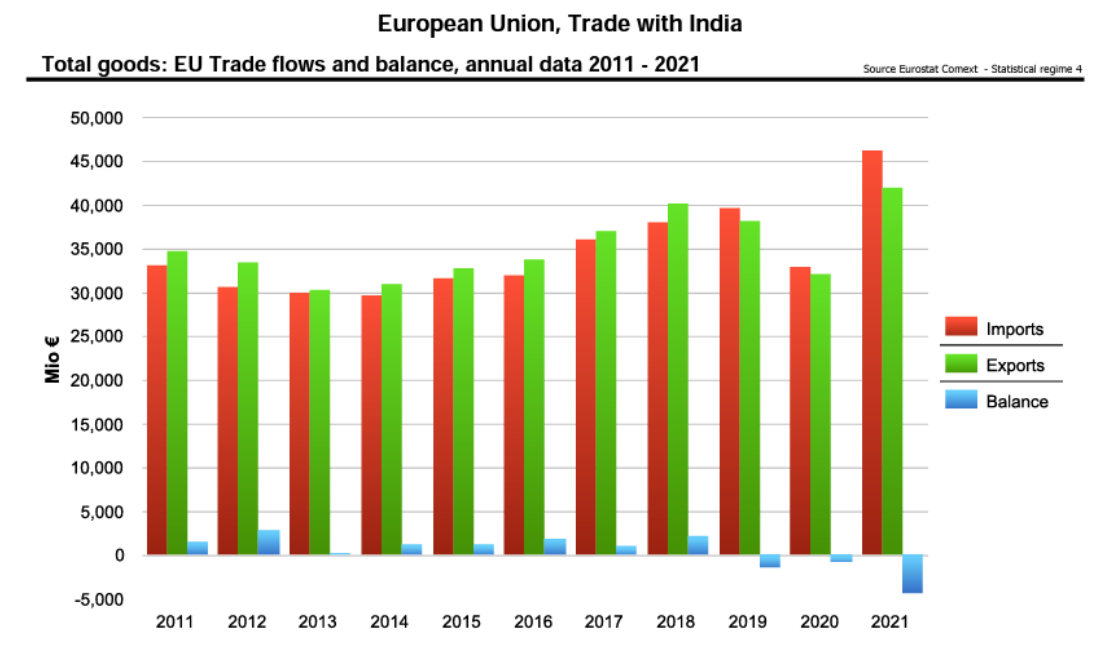

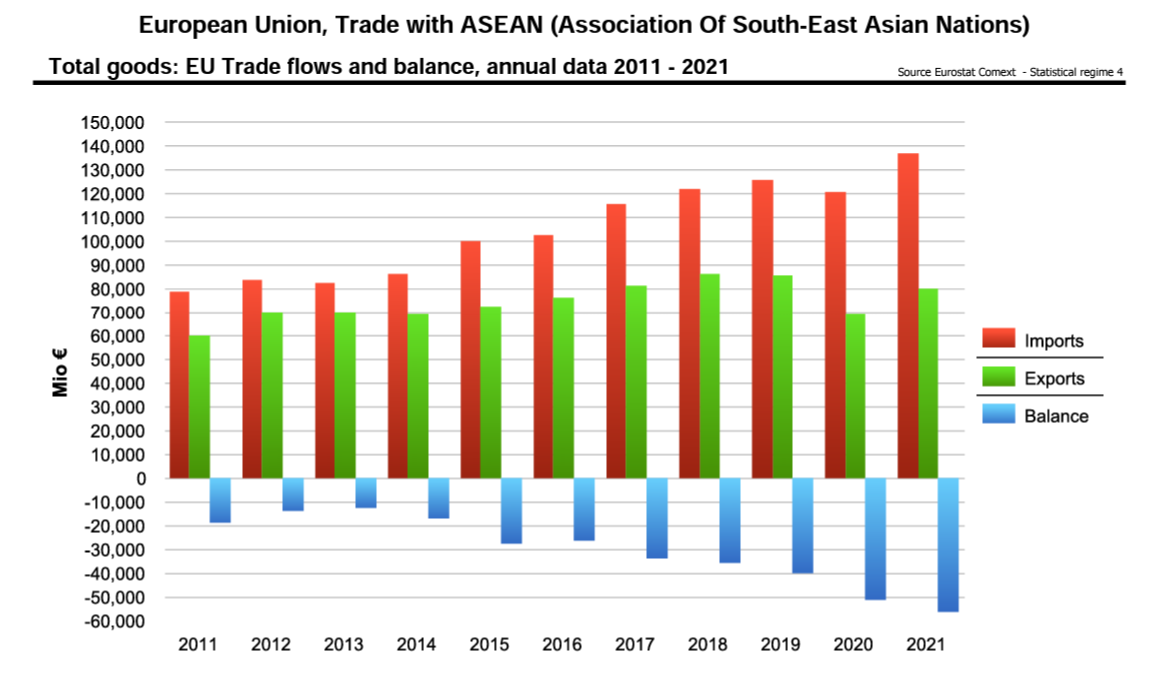

The EU’s ‘not in my backyard attitude towards the Chinese threat in the South China Sea and the Indo-Pacificshould change through reduced dependence on China for critical supply chains. In 2021, for instance, the EU’s bilateral trade with China was approximately six times that of the EU’s bilateral trade with Japan, almost eight times that of bilateral trade with India, and almost thrice it’s bilateral trade with ASEAN. Overall, the EU’s bilateral trade with Japan, India and ASEAN combined is still only approximately 60% of the EU’s bilateral trade volume with China. The trade figures (vide figures 1, 2, 3 and 4) establish without doubt that the EU has a bread-and-butter relationship with the Chinese. The dependence of the EU on Chinese goods is a crucial factor contributing towards the EU’s soft attitude towards the China threat in the Indo-Pacific.

Figure 2: Trade between EU27 and Japan

Figure 2: Trade between EU27 and Japan

Figure 3: Trade between EU27 and India

Figure 3: Trade between EU27 and India

Figure 4: Trade between EU27 and ASEAN

Figure 4: Trade between EU27 and ASEAN

Following the Russia-Ukraine war and the coerced unity it generated in transatlantic and European relations, there has been a perceptible shift in the EU’s approach towards the problem of overreliance upon China. For instance, the recent engagement of the German chancellor with his Indian counterpart vis-à-vis cooperation in green energy, security and defence, and trade is a case in point. The EU can explore cultivating deeper economic integration with India through bilateral trade and investment treaties. Advancing relations with India and other like-minded countries would be a good step towards creating a diversified supply chain. A diversified supply chain could further reduce over-reliance on Chinese supply chains. Reduced reliance will ensure that the EU focuses more on the values it holds dear, such as freedom of navigation and rules-based international order which have taken a back seat in the presence of bread-and-butter issues in its relations with China.

The Indo-Pacific has emerged as a theatre for the EU’s cooperation with partners such as India, ASEAN, Japan, South Korea and Australia. It is also an arena where the ground is ripe for the EU’s partnership with the USA. However, the AUKUS deal has thrown open some challenges for the EU. The EU, especially France, is concerned with the trilateral pact between the USA, the UK and Australia because the pact would alter the relative balance of power in the region. Given the scale of the nuclear submarine deal, AUKUS will also have deep implications for the economics of defence exports. France, having lost out on the deal, is concerned about this development. While the concerns of the EU are not without merit, the EU must realise that the Indo-Pacific is beset with an imminent threat of disruption of the rules-based order. Furthermore, the objectives of AUKUS are consistent with the broader strategic goals of France and the EU. AUKUS is merely a tactical setback for the EU. In the strategic sense, the AUKUS may even emerge as a thread that connects the Indo-Pacific and the Transatlantic.

This essay argues that the AUKUS-related developments, and the developments precipitated by the Russia-Ukraine war, further strengthen the case for the EU’s cooperation with the Indo-Pacific with renewed vigour. Cooperation with an enhanced sense of strategic clarity and recognition of the China threat is a crucial lesson. Another lesson this essay draws from the milieu is the importance of heightened investment in the future of the European military. China will continue to create whirlpools of belligerence in the Indo-Pacific, and the USAwill likely continue pivoting towards the Indo-Pacific. In such a context, a militarily strong EU will have more options to ameliorate its security situation, deeply influence world affairs, and preserve its strategic autonomy. The final lesson that this essay would like to draw is that there is a need to have a common European policy towards China. Currently, the EU nations have a differing, if not divergent, outlook towards China. For such strategic clarity, the EU would need to reduce its overreliance on Chinese goods and craft a non-China-centric Indo-Pacific policy.

Just like COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war have become the world’s most disruptive challenges, so can Chinese belligerence in the Taiwan strait, South China Sea and East China Sea become the world’s problem in the future. The Charybdis of the Indo-Pacific has the potential to create such enormous whirlpools across the world’s oceans that it can suck in Europe too. Therefore, the ‘not in my backyard’ attitude needs to be addressed urgently for a more goal-directed implementation of the Indo-Pacific strategy through partnerships with like-minded countries that respect rules-based order.

The EU’s Arctic Turn

Finally, the Arctic has been described by the document as a key strategic priority. The EU hopes to ensure that the Arctic does not emerge as an arena of tension and calls for a rules-based legal framework for cooperation in the Arctic region. The focus in the Arctic is not confined to geopolitical rivalries alone but is broad-based owing to the centrality of climate goals. However, the Arctic has emerged as an arena of competition, and geopolitical rivalries have spilt into the Arctic. For example, following the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the EU released a joint statement with Arctic countries like Iceland and Norway to suspend all engagements with Russia and Belarus under the Northern Dimension policy. Similar suspension of engagements has been jointly undertaken by the EU and the Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS). Thus, competition for influence and resources also lurks in the ecologically sensitive Arctic region.

Although China is a non-Arctic country, it has shown resolve to influence affairs in the Arctic and gain a stronger foothold in the region. China’s deep cooperation with Russia must be watched even in the Arctic. However, China is a major player in the world’s quest towards a more sustainable future, and the ecologically fragile Arctic region cannot afford geopolitical competition. The ecological fragility of the region necessitates rules-based order in the Arctic and global cooperation to achieve that. The Arctic is, therefore, rightly highlighted as a major regional priority in the EU’s strategy.

The Path Ahead

Given the growing instability in the international order, the EU’s external policy actors ought to be very watchful. While the European Union faces the Scylla at its doorstep, there’s a Charybdis of equal or greater magnitude creating whirlpools in the Indo-Pacific. The assessment of regional threats ought to undergo continuous appraisal and the strategic priorities should be appraised accordingly.In addressing the threats close to the EU, the bloc needs to be watchful of the activities of the Chinese not only regarding the Russia-Ukraine conflict but also across themes such as rules-based order, weaponisation of trade, and freedom of navigation. In an apt appraisal of the situation since 2016, the EU has already identified China as “an economic competitor and a systemic rival”. Only deep engagement with democratic and like-minded powers in the Indo-Pacific can help tide over the systemic rivalry and threats to a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific.

References

Anand V, “Locating China in the Russia-Ukraine war,” The Hindu, February 09, 2023, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/explained-locating-china-in-the-russia-ukraine-war/article66491207.ece

AngeAboa and ThiamNdiaga, “France eyes Ivory Coast after Burkina Faso boots out French troops,” Reuters, February 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/france-eyes-ivory-coast-after-burkina-faso-boots-out-french-troops-2023-02-20/

“CELAC-UE Bi-Regional Roadmap 2022 – 2023,” European Commission, October 2022, avalable at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/221025infographicEU_CELAC-roadmap-clean.pdf

“Enter EU: The Challenges and Cooperation Potential of the Indo-Pacific Strategy,” EIAS, October 19, 2021, available at https://eias.org/policy-briefs/enter-eu-the-challenges-and-cooperation-potential-of-the-indo-pacific-strategy/#:~:text=The%20EU%E2%80%99s%20strategy%20for%20the%20Indo-Pacific%20prioritises%20Digital,regimes%20to%20create%20zones%20of%20free%20data%20flow.

“EU and Mercosur reach agreement on trade,” European Commission, 28 June 2019, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_3396

“EU Strategy for Cooperation In The Indo-Pacific,” European Commission, February 2022, available at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-indo-pacific_factsheet_2022-02_0.pdf

“EU support to the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States (CELAC),” European Commission, 26 October 2016, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_3542

“EU wants to send more people back to Africa, Middle East, Asia,” The Print, January 26, 2023, available at https://theprint.in/world/eu-wants-to-send-more-people-back-to-africa-middle-east-asia/1335992/

“EU wants to send more people back to Africa, Middle East, Asia,” The Print, January 26, 2023, available at https://theprint.in/world/eu-wants-to-send-more-people-back-to-africa-middle-east-asia/1335992/

“EU-China Relations factsheet,” EEAS, April 01, 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-china-relations-factsheet_en

“EU-India Strategic Partnership, EEAS, available at April 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EU-INDIA_Factsheet_2022-04.pdf

“EU-Republic of Korea Relations,” EEAS, June 30, 2020, available at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-republic-korea-relations_en

“European Union, Trade in goods with ASEAN,” European Commission, August 02, 2022, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/region/details_asean-association-of-south-east-asian-nations_en.pdf

“European Union, Trade in goods with China,’ European Commission, August 02, 2022, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_china_en.pdf

“European Union, Trade in goods with India,” European Commission, August 02, 2022, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_india_en.pdf

“European Union, Trade in goods with Japan,” European Commission, August 02, 2022, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_japan_en.pdf

“Many who support right-wing parties think European integration has hurt their nation’s economy,” Pew Research Center, October 9, 2019, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/the-european-union/pg_10-15-19-europe-values-04-08/

“Marc Filippino, Henry Foy and David Pilling, ” Russia’s ‘second front’ “, Financial Times, February 21 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/610808f9-8a99-4629-8d67-3ac9b8e651a1

“Michael Mahanta, “Mali says “Au revoir” to French interference, asserts independence in UNSC dealings,” TFI Global,March 11, 2023, https://tfiglobalnews.com/2023/03/11/mali-says-au-revoir-to-french-interference-asserts-independence-in-unsc-dealings/

“Northern Dimension Policy: Joint Statement by the European Union, Iceland and Norway on suspending activities with Russia and Belarus,” EEAS, March 08, 2022, available at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/northern-dimension-policy-joint-statement-european-union-iceland-and-norway-suspending_en

“Presidents of 8 EU states call for immediate talks on Ukrainian membership,” Reuters, March 1, 2022, available at https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/presidents-8-eu-states-call-immediate-talks-ukrainian-membership-2022-02-28/

“Presidents of 8 EU states call for immediate talks on Ukrainian membership,” Reuters, March 1, 2022, available at https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/presidents-8-eu-states-call-immediate-talks-ukrainian-membership-2022-02-28/

“Russia/Belarus: Members suspend Russia and Belarus from Council of the Baltic Sea States,” EEAS, March 05, 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/russiabelarus-members-suspend-russia-and-belarus-council-baltic-sea-states_en

“Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe – A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy,” European Commission, June 2016, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf

“SuhasiniHaidar, “India and EU Relaunch FTA talks, Sign Connectivity Partnership,” The Hindu, May 08, 2021, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/virtual-meeting-of-prime-minister-narendra-modi-and-european-union-leaders/article34515784.ece

“The Crisis in Sahel: New Challenges to European Security, European Eye on Radicalization, July 17, 2020, available at https://eeradicalization.com/the-crisis-in-sahel-new-challenges-to-european-security/

“The EU And Asean,” EU Cooperation – ASEAN project, available at https://euinasean.eu/the-eu-asean/

“Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) – Documents,” European Commission, available at https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/united-states/eu-negotiating-texts-ttip_en

Rakshit Mohan is the co-founder of The Reformist. He is a public policy enthusiast and an independent foreign policy analyst.